Though it dissipated on Nov. 4th, Hurricane Melissa left widespread devastation and loss in its wake as it passed through communities across the Caribbean. Investigations are still underway to determine the full extent of the damage, but much is already evident. The current death toll stands at over 90 people, with at least 45 deaths in Jamaica, 43 in Haiti, and more yet in the Dominican Republic. Homes, businesses and farmlands were destroyed; livelihoods were wiped out, and hundreds of thousands were displaced. Coupled with several people still missing and a growing homeless population, human loss has been severe.

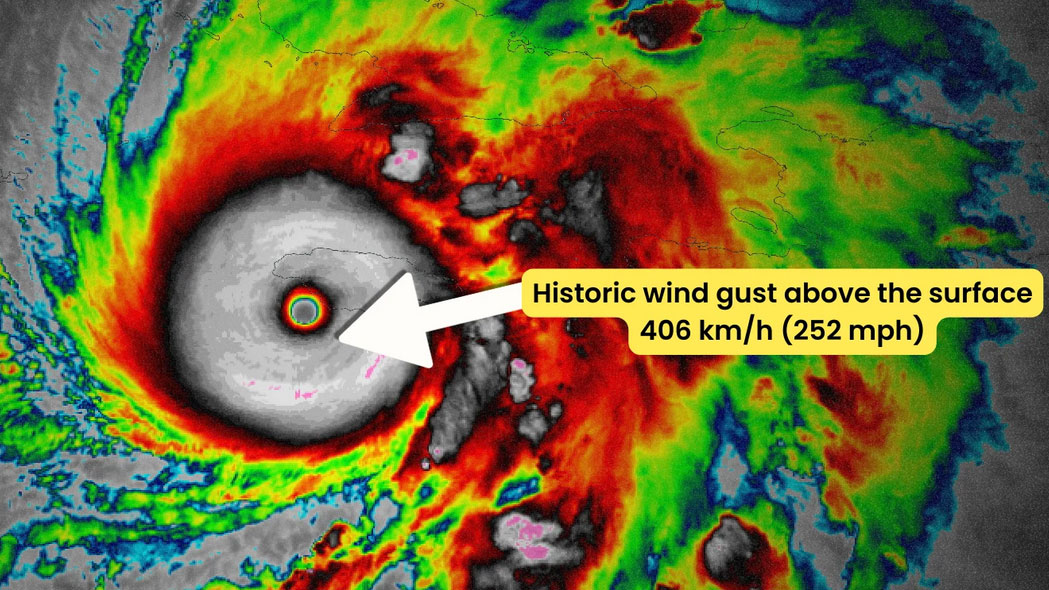

First originating as a wave off the coast of West Africa, Hurricane Melissa gradually organized and intensified during its path towards the Caribbean Sea, forming into a Category 5 hurricane that crashed into Jamaica’s southern coast on Oct. 28. The effects were instant and brutal, with intense rainfall and winds of up to 185mph (298km/h), the destruction of important infrastructure like roads, power grids, water and telecommunication lines, and a growing death toll.

A day later, Melissa weakened to Category 3 and moved towards Cuba, making landfall in Chivirico and causing significant flooding there and in neighbouring Dominican Republic and Haiti. The hurricane continued along its path, weakening as it passed through Bermuda and near Newfoundland before it finally dissipated. But the damage was done.

It was the worst climate disaster in Jamaica’s history, wiping out nearly a third of the nation’s annual wealth.

TRU student Annecia Thomas said her Parish, Westmoreland, was among the hardest hit in Jamaica, with significant infrastructure and agricultural damage caused by high winds, intense storms, and deadly floods.

“Westmoreland is where my dad’s from,” Thomas said. “Where he grew up, where most of my family, on his side, lives. My great-grandmother’s house is completely demolished. My uncle’s roof is gone. My mom’s roof is gone. We lost family members.”

Thomas, who is in her second year of a political science and economics program, described the struggle of dealing with the news while being so far from her loved ones and community members.

“I’ve had to take social media breaks,” she said. “It’s just so hard to see all the flooded roads, all the broken-down buildings. Places that used to be flowing rivers, so beautiful, now just full of mud, full of debris.”

Despite Melissa’s warpath, others, like third-year Journalism student Sam Weir, were more fortunate. Weir was born and raised in Canada, but is of Jamaican descent, with many close relatives still on the island. According to him, his family home (which has been in the family for around a hundred years now) was spared from the devastation. And, aside from some flooding that affected their farmlands, they were largely unscathed.

“They had some damage,” he said. “Just not as big as the damages that other parts of Jamaica suffered. Nothing that can’t be rebuilt.”

The same cannot be said for Thomas, whose family also lost many irreplaceable memories in the ruins of her great-grandmother’s home.

“We’re not going to find those again,” she said. “Those are gone forever.”

Still recovering from the particularly intense hurricane season the previous year, as well as other disasters over the years that significantly weakened their infrastructure, the Caribbean Islands have found themselves increasingly fragile and susceptible to massively devastating effects as the hurricane seasons come around annually.

With rebuilding efforts underway, students like Weir and Thomas are both dedicated to helping as much as they can, yet feel a sense of helplessness due to their distance and limitations.

“If I could go over there right now,” Weir said, “I probably would.”

“I get phone calls all the time about people wanting to help,” Thomas said. “And there’s not much we can do at this time. We’re just trying to figure out these fundraisers, you know? It’s like a continuous battle just to try to do what we can.”

This doesn’t mean that nothing is being done. The Jamaican government approved a 30-day tax waiver on specific goods being imported into Jamaica from other countries. Efforts have been made to send in vital items like diapers, tents, flashlights and bottled water into the country during this window. In Kamloops, Gateway City Church organized a relief fundraiser on Nov. 15, offering $20 plates of Jamaican food, with proceeds used to “provide food, supplies, and hope” to affected parties.

Of course, the elephant in the room is climate change. Studies have found that not only are hurricanes occurring more frequently, but the time between successive hurricanes is gradually contracting, leaving little space for significant infrastructural recovery before the next disaster hits. The cascading effects of these rapidly changing patterns are innumerable, ranging from social erosion and economic debt spiralling to the threat of total infrastructure collapse.

Due to climate change, winds of Melissa’s strength are now five times more likely to occur, per climate scientists. And intense rainfall like the kind that hit Jamaica for five consecutive days is now twice as likely and 30 per cent more intense.

“This was the worst one by far,” Thomas said of this year’s hurricane season. “They’ve never seen anything like this, and they weren’t prepared for anything like this.”

As a result of the deadly intensity of Melissa, many are calling for climate justice and accountability. Jamaica contributes less than 1% of global emissions but is severely affected by the effects of climate change.

“Places like Canada and the U.S. emit so much [greenhouse gases], while places like the Caribbean don’t,” Thomas said. “A majority of Jamaicans don’t have cars–they use buses or taxis, or they walk. They reuse things all the time. They own their own animals and raise their own chickens. Yet they’re some of the most affected by climate change and natural disasters. It’s unfair.”